When a broken gas pedal Went Missing

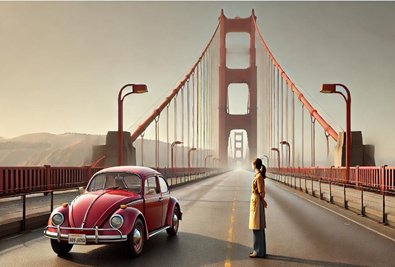

It was Monday morning in the summer of 1972, and I was 18 years old, feeling like I was teetering on the edge of something monumental. My ’62 VW Bug, Chili Pepper, growled as it climbed Waldo Grade, sounding as determined as I felt. It was my second week at my first grown-up job, and despite the nerves buzzing under my skin, I blasted KFRC on the AM dial. A Horse with No Name crooned through the static, and I sang at the top of my lungs, using the steering wheel as a makeshift microphone.

It was Monday morning in the summer of 1972, and I was 18 years old, feeling like I was teetering on the edge of something monumental. My ’62 VW Bug, Chili Pepper, growled as it climbed Waldo Grade, sounding as determined as I felt. It was my second week at my first grown-up job, and despite the nerves buzzing under my skin, I blasted KFRC on the AM dial. A Horse with No Name crooned through the static, and I sang at the top of my lungs, using the steering wheel as a makeshift microphone.

I’d dressed with care that morning, hoping to impress. A burgundy pleated skirt hugged my hips, a paisley bell-sleeved blouse with a butterfly collar whispered sophistication, and my hair was styled in a perfect bun, courtesy of a tutorial in Seventeen Magazine. I was a portrait of someone trying—desperately—to belong. The plan was simple: shed the wild, feral child I’d been and mold myself into a polished, respectable adult.

But no plan survives first contact with the world, and mine was already fraying. My history was a tangle of trauma and survival. In the early ’60s, my parents, distracted by their own personal dramas, abandoned my brother, sister, and me in Mexico. For years, I became their de facto parent, barely holding us together, but grateful for the generosity, joyfulness, and love of the Mexican people who say, en las malas se conoce a los amigos (in bad situations is where you know who your friends are). When our mother finally came back in 1969, spurred more by the fear of religious judgment than maternal instinct, she hauled us back to the U.S. The transition was brutal. I was a stray dog trying to pass as a show pony.

Life had taught me to fend for myself. I’d patched together odd jobs to buy Chillie Pepper, a car as scrappy and stubborn as I was. It wasn’t just transportation; it was survival. I learned to measure gas levels with a yardstick and coaxed the finicky starter back to life with a screwdriver when it failed, often in the worst possible places.

SKIRTING CATASTROPHE

One of the worst places? Highway 101, on a rainy afternoon. Chillie Pepper hit a patch of standing water and spun like a tilt-a-whirl across three lanes of traffic. Before I could even scream, I collided with a CHP cruiser, pinning it against a chain-link fence.

When the world stopped spinning, the officer emerged from the crushed vehicle, his face as pale as the overcast sky.

“Are you hurt?” he asked, his voice tight.

I shook my head, my breath hitching in my throat. “No,” I croaked, though my hands trembled so hard I had to grip the steering wheel to steady them.

The officer exhaled, shoulders sagging with relief. “Nothing hurt but your pride,” he said gruffly, trying to make light of it. But before the weight of his words could settle, another car hydroplaned, skidding straight into the cruiser, finishing it off.

Some days, you’re just grateful to walk away.

THE GOLDEN GATE AND THE GAS PEDAL INCIDENT

That morning on the bridge, I felt unstoppable. I honked along with my fellow commuters, a solidarity of steel and rubber. But as I emerged from the tunnel, the Golden Gate was swallowed by the dense fog. Typical San Francisco summer.

The toll plaza loomed ahead, and I joined the sluggish crawl of cars. My chest tightened as I glanced at my Timex, winding it with nervous fingers. I couldn’t afford to be late, not again. Finally, I rolled up to the toll booth.

The attendant was a young guy with a Frank Zappa mustache, the kind of wannabe rebel who oozed false confidence. He winked, and I felt a small spark of validation. For a moment, I wasn’t just another commuter. I was seen.

I reached into the ashtray for my 50 cents, but I found myself clinging to a bar next to a guy in a three-piece suit, who glanced at me like I was contagious.

as I pressed the clutch to shift, my foot hit nothing but floor. My heart stopped. I blinked, then blinked again. Where the hell was the gas pedal?

Panic surged through me like wildfire. I slammed the car into neutral as horns blared behind me. Leaning over, I spotted the gas pedal on the floorboard, mocking me with its oily grin.

“What’s wrong?” the toll-taker asked, leaning out of his booth.

“My gas pedal fell off!” I blurted, my voice cracking with a mix of disbelief and rising hysteria. His eyes widened, and he asked, “It fell off?”

I nodded, fumbling with the greasy pedal, trying and failing to reattach it. Sweat slicked my palms as the honking began to sound like a flock of seagulls fighting over a dropped hot dog bun. I could feel the eyes of every driver behind me, their impatience slicing through the fog.

Suddenly, a booming voice cut through the chaos: “RELEASE YOUR EMERGENCY BRAKE.”

A tow truck had pulled up behind me, its massive front grill filling my rearview mirror. Without thinking, I did as I was told. Chillie Pepper jolted forward as the tow truck nudged me through the toll gate. Relief and humiliation warred within me as I waved a feeble thanks to the toll- taker.

KINDNESS IN UNEXPECTED PLACES

The tow truck pushed me to a small gas station on Lombard Street. Two attendants, Amal and Zafar, stepped out of the service bay, and walked towards me after crushing their cigarettes. I explained my predicament in a shaky voice, and asked if I could park my car there until I could figure out what to do next.

Zafar nodded. “Sure, no problem. You park here. No charge, just leave key.”

Their generosity stunned me. In my world, help always came with strings. But here, in this grimy gas station, two strangers showed me the kind of kindness my own family had rarely afforded.

THE WORKDAY THAT ALMOST WASN’T

By this point, I was so late for work, I figured I’d already been fired. But I had no choice but to figure out the bus system, something I’d never done before. So, I made my way to the nearest bus stop and drilled the driver with a barrage of questions. The poor guy looked like he wanted to throw me off, but I wasn’t about

to let that happen. I needed to get to South City, even if it took all day. Work is still owed to me for the previous week.

My neat bun had unraveled into a nest, and the flowers in my hair were wilted casualties. My clothes were wrinkled, my nylons torn, clinging to a bar next to a guy in a three-piece suit, who glanced at me like I was contagious. My hands were greasy from trying to fix the pedal, and when a window seat finally opened up, I slid into it and started rubbing my hands together, hoping to spread the dirt around enough to make it less noticeable.

As the bus rattled down Van Ness, I started testing myself, reading the street signs ahead. Filbert. Union. Green. When we passed Bush Street, the Ellis Brooks jingle popped into my head:

“See Ellis Brooks today, For your Chevrolet,

Corner of Bush and Van Ness! He’s got a deal for you,

Oh, what a deal for you,

A Chevy deal that you will like the best!”

“A Chevy deal, yeah, right”, I mumbled to myself. “Fat chance anyone has a deal for me – and besides, the God damn jingle doesn’t even rhyme!”

At the south of Market Street transfer station, I boarded my last bus. The driver, an older- looking woman with a wide girth, watched me drop my money in the slot as though I was about to cast a spell on her. “Well, I was gonna give ya a dirty look first, but ya already got one,” I snarled. The heavy commuter traffic had dwindled, and I had no problem finding a window seat. I sat looking out the window and thought, even if I was able to save my job, what would I do about transportation? If I could afford another car, which I couldn’t, and the chance of getting a car loan, let alone a checking account, was as likely as hearing a cat bark, the Equal Credit Opportunity Act was still two years away.

My stop was coming up, and I started walking up to the front of the bus. Standing just behind the driver, I looked at my reflection in her rear-view mirror, my neat bun that sat on my head now looked like a roller coaster derailment, and the flowers were now carnage that had not yet been swept to the curb. The door opened, and I started down the steps, then stopped and turned back to the driver and said, “I’m a work in progress.” The driver chuckled and seemed to accept my off-handed apology for mouthing like my daddy, then said, “Ain’t we all girl!”

By the time I stumbled into the Girl Scouts’

I could almost hear her squeaky voice reciting Sam Walter Foss’s poem The House By The Side Of The Road.

office, I was a mess. My neat bun had unraveled into a nest, and the flowers in my hair were wilted casualties. My clothes were wrinkled, my nylons torn. I braced for reprimands, but instead, the women welcomed me with open arms. They offered tissues, water, and a moment to collect myself. Their compassion was almost too much to bear. I was used to judgment, to people pointing out my flaws as though I needed the reminder. But these women just wanted to help. I threw myself into work, grateful for the monotony of the mimeograph machine. The rhythmic churn of its rollers drowned out the day’s chaos, giving me a rare sense of control.

A RIDE AND A REVELATION

Later, Ann, a coworker whose life seemed just as messy as mine, offered me a ride back to the city. She unloaded her story about how her husband had recently come out, how their marriage was dissolving under the weight of truths too long buried. I listened, nodding along, recognizing the ache of living a life that doesn’t fit the narrative others expect. I could relate, I felt like one, a faker, trying to climb down from the feral limbs of a family tree. Whenever I was asked what my father did for a living, I crossed my fingers and told them he was in import/export because it was more palatable than saying he was a gun smuggler.

When we reached the gas station, Chillie Pepper was waiting, and to my surprise, her gas pedal had been restored through the generosity of Amal and Zafar, with the condition that I would buy my gas at their station. I pulled away, with their act of kindness buoying me in a way I hadn’t expected.

That night, as I drove home to my rented room in San Bruno, I thought about the day’s events. My family’s religion had painted the world as a hostile, sinful place, full of people waiting to lead me astray. But my new friends, and the strangers I met— Amal, Zafar, the toll-taker, even the tow truck driver—had shown me a different truth. The world was messy, yes, but it was also full of people willing to help without demanding allegiance.

EPILOGUE

As I lay on my lumpy mattress in the dark, sleep stubbornly eluded me. In the distance, the faint sound of a train whistling carried through the night, stirring memories of my grandmother. I could almost hear her squeaky voice reciting Sam Walter Foss’s poem The House By The Side Of The Road.

The events of my day played like a reel in my mind, a testament to the poem’s wisdom. Contrary to the fire-and-brimstone warnings I’d grown up with, there were people in this world who chose to live as friend to all, offering kindness without judgment. I began tallying the faces of those who had crossed my path on this rough road—there were dozens. Their small acts of grace comforted me, wrapping me in a sense of belonging. I felt blessed, even loved.

But beneath the warmth of their compassion, I knew the truth: I was the navigator of my own journey. If I were going to pull myself up by my bootstraps, I’d need a solid pair of boots, maybe black cowboy boots with a phoenix overlay, a fitting symbol of resilience and rebirth.

PS:

I continued to buy my gas from Amal and Zafar. I met their new babies as they came along, until they sold out to a name-brand gas company and bought a house in Marin County.