Left is Right and Right is Wrong

I was couch surfing after abruptly leaving home at seventeen. Though I’d been back in the United States for three years, I hadn’t made a single ally. Friendships outside the confines of the Kingdom Hall were strictly forbidden, not that I had much interest in high school friendships anyway. The other students found me “freaky-deaky,” and I found them dull and childish. My options for companionship were slim at best.

I was couch surfing after abruptly leaving home at seventeen. Though I’d been back in the United States for three years, I hadn’t made a single ally. Friendships outside the confines of the Kingdom Hall were strictly forbidden, not that I had much interest in high school friendships anyway. The other students found me “freaky-deaky,” and I found them dull and childish. My options for companionship were slim at best.

My mother, ever meddling, had been scheming with another sister in the congregation to pair me with her 27-year- old son, Brian, a man she deemed “elder material.” The idea made my stomach churn. Too many Saturdays, he muscled into our car group of mostly teenagers. As we bounced along the winding roads between Sebastopol and Occidental, peddling Watchtower and Awake! magazines for a nickel apiece in Brother Lent’s blue ’68 Plymouth Baracuta, Brian regaled us with his ideas about “training a wife while she’s still young.” It wasn’t just his wonky eye or the fact that he shaved his entire 6’4” body—it was his mindset. The thought of being stuck with him as a husband for the rest of eternity made me sick to my stomach.

My mother viewed herself as both a martyr for what she had endured from my father and a savior for eventually returning to Mexico to retrieve three forgotten children. I saw her as a millstone dragging me down. She forbade me to mention college; instead, she hammered down on me about marriage. I felt suffocated; I longed to return to Mexico, where I had a staunch support group and the opportunity to make my own decisions and plan my future. Life at home became unbearable. At the Kingdom Hall, Brian’s mother narrowed her eyes into tiny slits, stared at me from across the room, and whispered from the corner of her mouth to anyone who would listen about how I had given up the opportunity of a lifetime. My mother constantly reminded me how I had disgraced her—after all she had sacrificed. It had all gotten to be too much.

Jack and Lance smelled perpetually of hard liquor and motor oil, a testament to their vices.

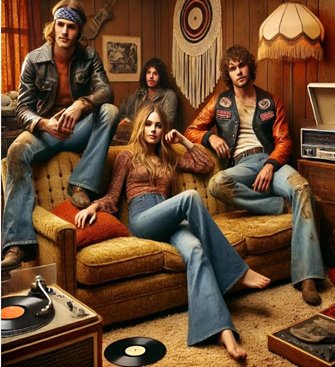

When I fled home, my stepfather’s nephew, Jack, took me in. Jack was a self-proclaimed religious outcast who had found his tribe among the black leather jackets and roaring choppers of Sonoma County’s biker scene. He was lanky, with straight blond hair that now grew down his neck. He had what one might call a Roman nose, casting shadows over his goatee, and he wore a single earring made from a nickel featuring Thomas Jefferson’s silhouette. A fresh tattoo adorned his forearm, marking his allegiance to his chosen family and a permanent break from the religion we had both grown up in.

Jack rented a duplex he shared with Lance, a guy he’d met at work. Their slumlord didn’t seem to care that the house reeked of two-stroke oil or that its two bedrooms served as storage for stolen bike parts—necessity knows no law.

Jack and Lance smelled perpetually of hard liquor and motor oil, a testament to their vices. Yet, contrary to what outsiders thought of them, they never pushed their habits on me, although I learned how to clean seeds and stems on an album cover and roll a decent blunt. Jack got me a job at Fast Gas, a 24-hour four-pump cut-rate gas station on Gravenstein Highway, after Lance was fired for passing out in the pay booth one night while on “reds.” It didn’t take long before half of Sebastopol was lining up at the pumps for “free” gas. By the time the morning shift arrived, there wasn’t a single pack of cigarettes or a cent in the cash drawer. Lance rebounded quickly, finding work on a fish-packing line, adding the scent of brine and fish guts to the collective aroma of their home.

Barbiturates were Lance’s likely drug of choice. He might’ve been in his late twenties, but it was hard to tell. His 501s were stiff enough to stand up in the corner of the room. His chopper spoke volumes— its sissy bar doubled as a sheath for a three-foot sword. Lance was an enigma, rarely speaking of his past. He gave the impression he’d rather crawl into bed with death than carry on a conversation.

THE PIERCING INCIDENT

Late one night, as was often the case, I had the duplex to myself. I rinsed out a Yosemite Sam glass from the sink, poured it half full of Annie Green Springs Peach Creek wine—a slight step up from Boone’s Farm—and popped a Doors 8-track into the stereo. Wrapped in a heavy cotton sleeping bag, I stretched out on the faded, forest-green plaid couch, its loose springs groaning under me. As Jim Morrison’s voice floated through the room, I wondered how much time I had before Armageddon knocked.

My reverie ended when the front door banged open. Jack and Lance stumbled in with a clean-cut guy who looked like he was in his mid-twenties. They were drunk, loud, and energized. The newcomer slurred out a question: “Will it hurt?” Jack, ever the showman, assured him, “Nah, I’ve done this a dozen times.” He turned to me. “Boil some water,” he ordered.

The old electric stove hissed as I cranked it on, the coils emitting the rancid scent of burned grease. While the water was heating up, I wrapped ice in a kitchen towel and handed it to the guy so that he could numb his ear. Behind me, I could hear Lance slamming cabinet doors, searching for a potato, and muttering about needing one for the job. But the kitchen was barren, except for eggs, bacon, and white bread. Defeated, he poured whiskey into three dirty glasses and passed them around.

The guy hesitated, removing his leather jacket to reveal his arms. Below the sleeves of his crisp white T-shirt, he bore tattoos that looked more like works of art. One arm had a tattoo of a rope wrapped around an anchor with a flock of seagulls soaring gracefully above, while the other displayed a lovely Asian woman with a straw hat, her shoulders balancing two baskets on a wooden stick. The details were stunning, far from the crude jailhouse scribbles Jack and Lance wore.

As the guy debated, he repeated, “Left is right, right is wrong,” over and over, as if the words were a mantra. Jack, increasingly impatient, snapped, “Do you want this or not?”

“Fine,” the guy said. “But left is right, right is wrong. Don’t mess it up.”

Lance declared, “We need a needle and thread.” I retrieved my sewing kit from the corner of one of the bedrooms, where I kept my prized possessions: a 1950 Featherweight Singer sewing machine and a handmade leather satchel that held my clothing. I handed over a needle and a spool of yellow thread.

By then, the water was boiling, the rancid smell of the coils fading. Lacking a potato, Lance grabbed a grimy hand towel from the bathroom and wadded it into a ball. Jack pressed it against the back of the guy’s ear, ostensibly to keep the needle from pushing through his head.

As People Are Strange played in the background, I couldn’t help but wonder why this guy hadn’t just gone down to the Coddingtown Mall and got his ear pierced at Claire’s Boutique, where all the high school girls, including myself, went for the low price of medical-grade studs. But maybe that’s precisely why he didn’t want to go there. Tough images are fragile things.

Lance and Jack stood around the kitchen table. The guy gave his final reluctant nod. As I watched, Jack plunged the needle through the guy’s ear. The scream that followed could’ve raised the dead. As the guy touched the thread dangling through his ear, Jack grinned. Then his face fell. “Shit,” he muttered when he realized he had pierced the ear to his left and not the guy’s left. “I pierced the wrong ear.” Without missing a beat, he added, “Might as well do ’em both, just to be sure.” And he did.

EPILOGUE

I never saw that guy again. Jack said his leave was up, and he shipped out of San Diego soon after. The Vietnam War still had four years to go. I didn’t even know his name, but his mantra stuck with me: “Left is right, right is wrong. ” It was not until years later that I realized that the location of a piercing was a code used to identify a straight man or a gay man.

Watching Jack pierce his ears, I realized how much of life is shaped by perspective. Jack stood across from the guy, making his left the guy’s right and vice versa. Both were correct from where they stood, yet both were wrong. At seventeen, that night taught me that decisions—and mistakes—often look different depending on your vantage point, as was the case with my mother, who fervently believed the elders who preached that Armageddon was “fast approaching” and predicted it to land on our doorstep in 1975. She believed my chances of survival would be far greater, almost assured, if I harnessed myself to an elder, as she did to my sept-father.

Sometimes, the bravest thing you can do is make a choice, knowing you’ll likely get it wrong but doing it anyway. That’s how you learn. That’s how you grow.